"I want to build up this all-American quarterback, this hero. This wonderful, beautiful kid with his entire future ahead of him. His biggest decision in life was whether he was going to take a full ride to UT or Notre Dame. He's got the hot girlfriend. He's got the loving parents. And he's going to break his neck in the first game. We're going to create this iconic American hero, and we're going to demolish him."

As the hours wore on and we encountered diversion after diversion, mechanical failure after mechanical failure, I did think, "Wow, it's not a good sign that we are now explicitly discussing how we will divide up the labor when we have to form a new desert-island society in the style of LOST."

When we briefly deplaned in Baltimore, the enraged solipsist left our little band of brothers/proto-society in a cloud of luggage-oriented recrimination. But before he did, he got the number of the woman sitting next to him, who had been parroting his every gripe like Echo and Narcissus for the last three hours. "Should I give you my number or my email?" she asked anxiously. He shrugged, and began grinding his teeth in the general direction of the gate agent. "Which would you *like*?" she persisted. "Whatever," he replied, focusing his glare on a pilot who was emerging from the gate, "This is insane. UNACCEPTABLE!"

"Are you kidding me?" I thought, "Who picks up women while behaving like a tool? Who consents to be picked up in these circumstances? What about this experience made you think, Now THERE's a guy I want to spend more time with. Maybe even the rest of my life"?

Happy Solstice. They're all getting longer from here.

Fragments from holidays with my nonna, who, at 91, is the most entertaining person I know.

Taking my grandparents home from Thanksgiving involves painstaking choreography to establish everyone safely in the car. "Watch your head, Watch your head, WATCH YOUR HEAD, ok, wow, very deftly handled," I say to my grandmother as she lowers herself into the passenger seat. "Yes," she replies, "but now I appear to be losing my pants." "That's just the sign of a successful Thanksgiving," I say confidently. We're nearly home by the time we stop laughing.

* * *

And my grandfather's no slouch in the hilarity department, although somewhat less intentionally than my nonna. The other day, I got this report from my mother: 'Tried to explain Occupy Wall Street (Nova Scotia, DC, St. Paul's London, Oakland, Portland, etc. etc.) to my nonagenarian parents. Finally, my father said, "wait, was this during the Depression?".'

* * *

In this holiday season of creches and carols, I always think of my grandmother's quest to find a single painting of the Holy Family in any of the world's major galleries depicting Joseph engaged in domestic labor or, more pointedly, childcare.

"Oh sure," she would say, "he'll do a bit of carpentry or tend the donkey. But meanwhile Mary's got her arms full of books and Jesus and sometimes John the Baptist for good measure. Do we ever see him change a diaper, read a story, or play with the baby?".

She was indescribably delighted when she finally found a late Renaissance image of Joseph making what appeared to be an omelet.

* * *

This recalls to me some summertime tales of my grandmother that I don't believe I ever told here. It all started with brunch at Great Falls with my grandparents. A drink arrives for me.

Grandmother: "What *is* that?" [She's having a mimosa.] "Did you order it?"

Me: "Er, yes. It's a Coca Cola."

Grandmother: "That's amazing. It looks extraordinarily like a *Coca Cola*."

Me: "It's extraordinary, yes."

Grandmother, with quiet disgust: "I just couldn't imagine any daughter or granddaughter of mine ordering such a thing."

Conversation, needless to say, unfolds naturally from that point.

My grandmother: "I so admire how you keep up with friends from all different times of your life."

Me: "Oh, well, I'm not that good. It's just easier in the age of Facebook."

My nonna, darkly: "Maybe TOO easy."

Me: "Uh, what do you mean by that?"

My nonna, who's never been on Facebook except to be shown pictures by my mother: "People feel free to post the minute details of their day, and its nothing but trivia."

Me: "Well, but there's..."

Nonna: "Trivia!" [Now she's really yelling.] "TRIVIA!!!"

Me: "I had no idea you felt so strongly...."

(We've had this same conversation several times since then. "How do you know this?" I ask her. She gives me a knowing smile and a sidelong glance: "People tell me things.")

On the way home from brunch, my grandmother doesn't care for the way another driver honks at us. So, naturally, this is what she says: "I don't know any rude hand signals. I must learn some. I think receiving a rude hand signal from a nonagenarian woman would be a very effective deterrent in situations like this, don't you?"

She immediately transitioned from this to telling me about witnessing her father have a heart attack (from which he shortly died) when she was a teenager. I'd never heard this story before.

It was a roller-coaster drive back from brunch.

Outside of a dog, a book is man's best friend.

Inside of a dog, it's too dark to read.

(Groucho Marx)

Often I find myself buying romances on the strength of a recommendation from someone I really trust. As with all other genres and art forms, my taste doesn't run so much towards particular sub-genres, tropes, and tones as it does towards innovation, quality, and complexity within a particular form. (This is how I got looped into romance reading as a literary scholar at all, not to mention comics, horror films, anime, reality dance competitions, curling, etc.) So from time to time I just take the risk and buy while thinking that the less I know about what I am about to read the better.

And then I open up the ebook, and it has an adorable puppy on the cover, and I think, "Oh Jesus. What have I done." (I can't even make this last a question, so heavy is the weight of dread upon my soul at the sight of that cheerful furball.)

|

| Jean-Honore Fragonard "Girl with a Dog" (c. 1770) Dogs and erotics Seriously: what's this about? |

I'm troubled by the idea that dogs have an entrenched role to play in a certain genre of romance because they set out a silent, adorable and adoring model for love as faith. What the routinely skittish protagonists of a dog romance see in their canine companions is love that is patient and kind, love that does not envy, does not boast, and is not proud, love that does not dishonor others, is not self-seeking or easily angered, and that keep no record of wrongs. Love that always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres. Beautiful, Biblical stuff - the love of dog as a model for romantic love, which itself becomes a model for love of god.

But, curb the canine and call me Darcy, I myself prefer romantic love with a touch of pride about it. Not love as self-abnegating devotion.

There's a certain irony here: despite my initial stomach-churning sense of dread, I often quite enjoy a good dog-themed romance. One of my favorite authors, Jennifer Crusie, frequently features dogs in her books, and they are fully-fledged characters, with as much personality and autonomy as any of the human players in the drama. And certainly I am a sucker for the sentimentalization of animal-owner relationships, and perhaps this is why I so resent being manipulated by them when they are in less skillful hands (or more blatantly mobilized by publishers) - I will snuffle into my drink about an ill-treated animal, but I'll also resent you for exploiting this empathy cheaply.

In Nikki and the Lone Wolf, Marion Lennox draws a vivid portrait of Horse, a massive and mistreated wolfhound who draws the hero and heroine from their homes one gothic night by howling inconsolably at the ocean. His owner threw him overboard to drown, but still he's faithfully waiting for this abusive scoundrel, and will be until the hero can persuade the heroine to take a dominant tone with the poor misguided soul (and thereby provide a new home, a new bond of love). Horse is a great character, as are his owners, but the resolution [SPOILER], which comes by way of a massive community-wide oceanic search for the beast, after he goes swimming off into the ocean like he's Edna Pontellier, desperate to find his mistress (who has herself, with irksome parallelism, stormed off in a fit of romantic pique), seems not just implausible but also exasperating. Is this the model of love we're looking at, I found myself asking, suicidal, irrational devotion that takes a village to soothe? If so, the hero and heroine are right to resist it.

*Is it piling on to talk about these silly titles? Admittedly this one is less egregious than the previous two in the series, Misty and the Single Dad and Abby and the Bachelor Cop, but it's the formula that gets me. Heroines get a name - a diminutive, early 90s identity - while heroes get a social role.

The term is finally over, and Mt. Grademore and I have cast conniving, sidelong looks at one another, packed our weighty selves into suitcases, and left for Hawaii. No kidding: Mt. Grademore on parade takes up half my freaking luggage. But now, after only four flights and a total of 27 hours of travel, here we are in sunny Oahu. And within 24 hours of arriving in Honolulu, I could already cross "hug a cylon" off my to-do list. Such is the benefit of having a partner who works on Hawai'i Five-0.

Best story to come into our lives recently as a result of D's time in Hawaii?

When D was last with me at Farfara (our new house in Nova Scotia), he got a message from the friend who'd been his replacement on the show for the previous three weeks. "I came back from a hike and started your car," it read, "but it was making a terrible squealing noise. When I lifted the hood, I discovered that there was a mongoose in your engine."

"In Halifax, do you occasionally find a moose under your hood?" asked one witty friend of ours, upon hearing this story.

"No," I replied, "but D did find a mink in the woodpile the other day."

"Mink in the Woodpile," chimed in another, "Best lesbian bar name ever."

I couldn't help it: "'Mink in the Woodpile, Mongoose in the Engine' sounds like the title of a conference paper I'd write." I paused to reflect. "It's subtitle would be 'Constru/icting Sexualities from Atlantic to Pacific."

"Mieux vaut un mangouste dans son moteur qu'un tigre (Proverbe Chinois du 3eme Millenaire BC)," intoned a French friend, who then sent me this video:

"Yup," I reply with caution, thinking (foolhardily) that I can wait him out.

I frown at the phone, but he can't see that, and I refuse to reward him with any audible sign of frustration.

Since this does move me from my taciturn stoniness, he expands on the point: "Have you heard about the giant Lego people who have been washing ashore? Google it. As someone who lives in a coastal community, it's important that you be prepared."

There was a period of time, between the ages of about 11 and 14, when I read Tamora Pierce's Song of the Lioness quartet dozens of time. I knew those books backwards and forwards, and their pleasure never waned upon rereading (although I certainly had least favorites in the series). Coming back to Pierce's books as an adult, I find there's more that makes me wince and wonder, but I'll never shake that sense that her characters *lived* for me at a particularly dramatic period of my life, underscoring the sense I had that my whole life was one of agonizing, awkward heroic possibility. Warrior possibility.

This feeling, this thrill of narrative possibility right in the pit of my stomach, is one I've never grown too cynical for, no matter how much time I spend reading Beckett nowadays. And I've spent the whole day in the grips of it after reading Moira J. Moore's brilliantly titled, atrociously covered Resenting the Hero. I took it to work with me and read it over lunch, hiding the very silly cover under a copy of Harold Pinter's collected works every time I heard footsteps outside my door. Then when people actually did come into my office, I couldn't stop myself from giddily pressing the book and its merits on them. When I finished the novel this morning, all I wanted was to pick up the next one. But I had ordered the hard copy, and it wouldn't be here 'til next week at the earliest. So I spent an hour painstakingly mowing another sixth of the yard. (I've

been back since August and I've almost finished the damn thing.) The whole hour all I could think about was going inside to buy the sequel as an ebook, rather than spend a moment without these characters. "Pull yourself together, Sycorax,"

I kept muttering, grass flying around me, "There are other books in the sea. Several thousand in your own library, in fact." The muttering's been a constant mantra throughout the day. I don't know how I'm going to last until next week.*

What we have here is sprightly, absorbing, deftly characterized and affectionately rendered fantasy. It's rich and warm and friendly, but I don't find it to be, as many readers do, as fluffy as the rep this section of the genre has acquired. Instead it feels lightly like Terry Pratchett, like laughter shot through with thought.

So much of the pleasure of the book is in the warmth of its characters' interactions that I almost feel like a plot summary does it a disservice. But I'll succumb: Dunleavy Mallorough is finally emerging from a lifetime of training to be a Shield, a graduation that comes only if she is chosen at a formal ceremony that feels like nothing so much as a middle school dance. The Shields have been kept apart from their future partners, the Sources, for the entirety of their training, to ensure that the moment they match (forming an unbreakable bond that can only end in death) comes only after both Shield and Source have sufficient training to do right by one another. So she finds herself in a long line of Shields, breathlessly awaiting the much smaller number of Sources, who move slowly down their ranks, waiting for the bond to snap into place like a minor earthquake.

From that moment, the Shield will be charged with the protection of the rare and precious Source, who is the odd individual who can channel natural forces through his (or her) body and mind, averting potential natural disasters and preserving the precarious societies of their land. In order to channel these forces, the Sources must drop all defenses, and in these moments the Shields step in to extend their own and regulate their Sources' bodily function. It's an intimate act: it demands minute attention to the habits and physiology of the partner. And its compensations have a sensual edge: pairs are sensitive to each other's touch, finding it soothing even if they can't stand each other. In turn, the Source is supposed to protect the Shield from one key area of vulnerability: a profound emotional sensitivity to music, which renders all the Shield's vaunted self-control almost completely moot. Sources are eccentric, given to bits of Shakespearean oddity in everyday speech, so being a Shield comes with a host of other caretaking responsibilities: writing up reports about channeling activity, defusing social awkwardness caused by the unworldly Sources, making the practical arrangements of travel. It's almost like being a servant. Or, in a old-fashioned, elaborately gendered sense of the term, a wife.

But not in any way that allows us to accept a genial stereotype of housewifery. Dunleavy (she prefers "Lee" with her friends, which is to say not with her Source) takes cranky pride in her duty, finding in the labor of a Source a sense of accomplishment and paradoxical self-sufficiency. Where the source can be flippant and thoughtless, the Shield must be serious, vigilant, practical, strong. Lee patrols the borders of her duties ferociously, and when she finds, to her dismay, that her bond snaps into place not with a sensible, earnest sort of person like her, but with a grinning, flirting hero like Lord Shintaro Karish, she's not convinced she will ever be able to trust the too pretty nobleman to do his duty by her. The more he tries to charm her (plain, fiercely accomplished old her), the less she likes him. The less she likes him, the less charming he becomes. And so we get a series of sparrings: screwball fantasy at its best.

The fact that it is so much fun shouldn't take away from the fact that it deals slowly and carefully with uncomfortable issues. The position of Source is lauded and privileged; the Shields, by contrast, are largely forgotten. They are enablers, always giving the necessary assist, never getting the glory. The entire legal and procedural structure of their jobs gives the Source power over the Shield. The Source determines their course, but isn't responsible for any of its practical execution. In fact, the Source's only responsibility is to restrain the Shield's excessive sensuality during encounters with music. Touch of the Cullen there.

So you can see that the relationship (in which, I hasten to note, either party can be any gender and sexuality is quite fluid) reads as both gendered and classed. Karish (who spends much of the novel trying to get Lee to call him Taro, since he despises his family name) is defined by privilege, both masculine and aristocratic, and the mercantile Lee has to work through the uncomfortable sense that she is endlessly vulnerable to exploitation, should he ever choose to exercise his power over her. In fact, the central conflict of the novel is generated by a villain who does a very convincing reading of the Source/Shield relationship as one of exploitation and oppression. If something goes wrong between a Source and a Shield, there is no possibility of divorce: the Shield in particular has no legal recourse in cases of negligence and abuse. The sinister nature of the mouthpiece doesn't mean that the critique of the system is any less valid; in fact, the political appeal of his argument (however cravenly he uses it to manipulate) is what makes him such a uneasy, Miltonian villain. (One of my rare complaints about the novel is how swiftly this plot line is resolved, and the extent to which the resolution occurs offstage, so to speak.)

So the real pleasure of the novel is in the rockiness of Lee and Taro's start, the slow and organic quality of their growing friendship (they truly have nothing in common besides mutual talent), and the way it is shot through with disruptive mistrust. Lee feels a wonderful ambivalence about the intimacy of the Shield/Source relationship, and the heroic charm of Taro specifically:

He looked at me, frowning. And then the frown turned into a smile that I didn't trust at all.

"You're staring," I pointed out tartly.

His response was to sweep up my free hand and kiss the back of it. In an instant every ache I'd been feeling was gone, so swift and so complete that the lack itself was almost painful.

I jerked my hand away, and the discomfort flooded back. (34)

This bit of affect(at)ion is a gesture that we respond to as readers, even as we see that it's something he does with many, many women he encounters. Lee doesn't know what makes her more uncomfortable: the idea that she could fall prey to Taro's indiscriminate charms (and be a romance stereotype rather than an individual worthy of his, and her own, respect), or the idea that she's been forced into a fated bond whose intimacies are beyond her control (another sort of romance stereotype, another sort of wiping away of individuality and free will). So her experience is a double ache: the pain of separation posed against the loss of selfhood that attends their pain-obliterating intimacy. An absence of pain that is itself an ache. A lack.

So... it's good. Perfect, engrossing thrill. But not mindless fun: as the title declares, it's going to take up a lot of conventions of the form, wring them by the neck a bit, embrace them, and send them on their merry way. And if you're wondering where I am at any point in the next week, I'm probably lying in wait by the mail-box, hopping up and down with nervous energy and trying not to reach for the Nook.

*The only thing bolstering my resolve is the revelation that, six books into the series, the publisher has abruptly dropped it. As if it weren't traumatizing enough that a series I love would end (NO!!!), now I hear that it's embattled. But Moore, who sounds like one of the most generous authors ever to walk the earth, has said she'll finish it and distribute it herself. Greater love hath no author. But knowing it is coming to an end, and that that final installment won't be available 'til next year, is helping me moderate my book gluttony.

And then we discussed Synge's The Shadow of the Glen, in which an elderly husband fakes his own death to test his young wife's fidelity.

I: "So he waits for her to begin inviting men to the house during his own wake. Who comes along first?"

Student 1: "Well, there's the shepherd, but first there's the tramp."

Student 2: "I thought that character was a woman for most of the play."

Students, as a group: "Yeah, me too."

I: "So you're saying that rather than imagining this as a play about hospitality and the impoverished wanderer, you read this as a commentary on the sexual politics of a young widow inviting a skanky woman to her husband's wake."

Students: "Pretty much."

I'm nipping back in to Sycorax Pine (although there's a huge pile of grading and course prep giving me a very cynical look out of the corner of its collective eye while I do so) to say a few words about last night's season finale of Doctor Who, to which I'm now totally devoted. If you don't watch the show, you should (start with the newest Doctor, Matt Smith, and then go back to watch from the beginning of this contemporary reboot, with Christopher Eccleston and then David Tennant.). But you probably will find what follows to be too elliptical to be truly spoilery. If you do watch the show, let me know what you think. (Be as spoilery as you want in the comments, and avoid them if you're spoiler averse.)

I thought this was a solid, if

unextraordinary finale. Unextraordinary, of course, only compared to the episodes the prodigiously clever Steven Moffat used to craft back in

the days when he had all the time in the world to work on a double-ep.

The characterization's what's paying the price for this current pace of apocalyptic plotting (the end is nigh! Silence will fall when the question is asked!), with less time than

necessary spent on the Doctor's relationship with River, and the companions

being shunted off to the side more and more as the season develops. The companionate relationship with River is now wholly perplexing (for us as for

them, I think, but their perplexity could be a lot more interesting than

it is right now). And Amy was right to call shenanigans on the whole

"luckily it all happened in an alternate time stream, so it carries no

ethical consequences" line that the show has often taken. Alternate timelines are a cheap out, and forgetting about them does the characters and audience a disservice.

I do love the Silence, though. Love 'em to death. (Love who to death?)

What happened in last night's

ep of Dr. Who does remind me of a structural problem I have with

seasons of True Blood, in which an interesting premise is often

established in the premiere, but then pushed to the point of aporia by

the finale. The problem is that (for

me) the chaotic disintegration of a world (apocalypse) is much less

narratively interesting than the character studies of real, detailed

lives placed under pressure by the insupportable inciting incident.

After all, apocalypse in these two shows is often an emptying out of

detail, place and character. A collapse of history.

I begin to worry that this means I've been reading too much nineteenth-century drama.

Ten days ago, I arrived home at Farfara from three months in London, Washington, and Honolulu (no pity's forthcoming, I know).

|

| These shenanigans don't sound like anything I would have been party to. I am a very dignified homeowner. |

Nine days ago exactly, I thought about the coming tropical storm, and forced my jet-lagged, befuddled self into the car to go grocery shopping in the now-distant town. It was a process, and I didn't make it home to unpack the groceries until 9 p.m. that night.

When I opened the fridge to discover the celery that D had left there three months earlier, I thought, "I'll just nip out to the composter with this!". I'm very excited about the composter. This is one of the ways I can tell middle age is bearing down upon me. It was only on the walk back that I realized my garden door had locked automatically behind me. And there was no key anywhere closer than Washington, DC, where I had left a spare with my parents. Less than twenty-four hours back, and I had locked myself out of the new house, in the dark, with the coyotes.

No keys, no phone, no car, no D, and it's now about 9:30 p.m. on a Saturday. What's more, I didn't have a lighting source to help me navigate out of our pitch-black 12 acres to the nearest neighbors.

So what should I do, like the intrepid adventurer I am, but pluck a solar-charged light-on-a-stake from the garden and flip-flop my way precariously down rocky, crumbling Farfara Way (as we punningly call my excessive driveway). It took about ten minutes of panicked stumbling in my minute silk dress before I was knocking on the neighbors' door. No answer. Panic rising.

I hear voices from across the street, by the ocean. Covered in dirt and brambles, I finally barge in on a large group of my neighbors (only two of whom I'd ever met), having a seaside bonfire party. (It's a weekly event in summer, I gather.) They turn to me, blinking into the shadows after the brightness of the fire.

"Hi, everyone!" I say, waving my glowing stake as non-threateningly as I can, "I'm your new neighbor from up the hill! I seem to have, er, locked myself out of the house...."

The next thing I know, my neighbors have broken out their ladders and are coming en masse in a line of vehicles to scale the sides of my house and break in through the screen windows on the second floor. (Forget that you ever heard me say that this was possible.)

And then they invited me back to the bonfire party, where they told me about the family of otters that have just moved in to our section of shoreline. I was there 'til after midnight.

Long story short: I love my neighbors.

[This piece may contain spoilers, and leans more towards analysis than review-as-recommendation. Proceed with caution, ye spoiler averse!]

The Earl of Kilbourne, newly home from war, is standing at the altar, luxuriating in rich clothing, abundant family, and the prospect of marrying his comely childhood friend Lauren, when there's a scuffle at the back of the church. A ragged girl struggles against those who are trying to remove her; she looks starved, impoverished, and like she spent at least one night in the open air. But looking at the beggar girl, he knows that she's his wife.

It had been a battlefield wedding. He'd promised his dying sergeant, her father, that he'd protect the spritely girl he'd come to like so much during the months of their campaign. But after just one night of marriage (one night... for love!), they were ambushed. As he saw her go down, he was shot himself, and when he regained consciousness his fellow survivors told him Lily had died. So, naturally, it seemed easier not to mention this impetuous marriage (to a commoner, no less) to his patrician family, what with their elaborate hopes of his future with Lauren.

It's a marvelously melodramatic opening - the battlefield urgency, the lost bride, the church door scuffle, the cries of recognition, the jilted friend! - and one whose excesses are balanced beautifully by the subtlety of the characters' ambivalence about their own decisions. When he first proposes to his late sergeant's very young daughter, Kilbourne's internal monologue is at least as interesting as what he says:

There's so much to admire about the emotional complexity of this passage. Kilbourne is unsure of his own motives, and all too aware that he might be bending ethics to the shape of the urgent moment. Is it fair to press an irrevocable decision - one in which she loses a wide array of rights - on a young girl in the middle of war who has just, hours ago, lost her father? He weighs this against the very great danger she will face if she remains a single woman and is taken prisoner, and, his decision made, still tries to preserve her autonomy of decision. But he's only too aware of the way desire colors his sense of the ethics of the decision. It is, as he later says, a balance between "the great impossibility" and "the obligation," or between the two senses of nobility. A gentleman would never be able to cross class lines so flagrantly for love (indeed, he would not be able to exercise the kind of matrimonial autonomy that war makes possible at all), but a gentleman would privilege his oath and his duty to friends and the vulnerable above social conventions with barely a second thought."I made him a promise," he tells her. "A gentleman's promise. Because he was my friend, Lily, and because it was something that I wanted to do anyway. I promised him that I would marry you today so that you will have the protection of my name and rank for the rest of this journey and for the rest of your life."

There is still no response. Has he really made such a promise? A gentleman's promise? Because it was what he wanted? Had he wanted to be forced into doing something impossible so that it can be made possible after all? It is impossible for him, an officer, an aristocrat, a future earl, to marry an enlisted man's humble and illiterate daughter. But doing so has now become an obligation, a gentleman's obligation. He feels a strange welling of exultation.

"Lily," he asks her, bending his head to look into her pale, expressionless face - so unlike her usual self, "do you understand what I am saying to you?"

"Yes, sir." Her voice is flat, toneless.

"You will marry me, then? You will be my wife?" The moment seems unreal, as do all the events of the past two hours. But there is a sense of breathless panic. Because she might refuse? Because she might accept?

"Yes," she says.

"We will do it as soon as we have made camp again then," he says.

It is unlike Lily to be so passive, so meek. Is it fair to her... (37)

The early part of the novel is wonderfully concerned (as many novels of the military historical sub-genre of romance are) with the ways in which the front can function as a sort of liberty or liminal zone in which normative, restrictive class and gender rules are loosened. Characters find that much can be excused by the assertion that it was war and measures had to be taken, quickly and decisively: "In the army he and Lucy can be equals," Kilbourne thinks, "They can share a world with which they are both familiar and comfortable.... But she can never be the Countess of Kilbourne, except perhaps in name" (39). War is both compelling and liberating: it forces the hand, but often does so in ways that defy normative pressures. So it is perhaps unsurprising that the second half of the novel, which takes place at the Earl's country estate and in London, is largely concerned with Lily's need to assert and protect her freedom and her husband's status. The battlefield marriage was romantic and sincere for both parties, but it was decided and accomplished under duress. When faced with the realities of being a countess, Lily both quails and resents.

The result is one that I've felt with every Mary Balogh novel I've ever read: a strong, even thrillingly nuanced opening with a conclusion that fails to make good on the stakes established early. There's always a point in her novels in which I stop and think, "Do I really need to keep reading?". Here the disappointment had a number of sources.

First, I was uncomfortably aware that the heroine's insistence on her need for freedom (in other words, her need to be free, so that if she comes back, she can come back to her husband on her own terms and as his equal) seems like a feminist stance for the book to take, but it may in fact be a false one. I am always wary of romance novels in which feminist individuation is a method of prolonging the narrative and creating tension. Since we are encouraged to long for a resolution, a HEA, this strategy places us as readers in conflict with the heroine's desire for independence, equality, etc. Unless the characterization is impeccably vivid and sympathetic, this runs the risk of creating a dismissive reaction. ("Honestly, can't she just pull it together so that they can be HAPPY already??") Our desire for the freedom of the heroine is placed in conflict with our desire for delays to be surmounted. Uncomfortable.

Let me give you just one example of this conflict of sympathies. At one point, Lily compares the subsuming effect of her marriage to her time as a POW, when she was repeatedly raped by a captor: "It was tempting. It would be so very easy to relax permanently into [Kilbourne's] kindness and his strength and become as abject in a way as she had been with Manuel" (102). On one level, YES. This is a fascinating way to think about how the soft loss of selfhood can be as insidious as its brutal theft. On another, REALLY? Being married to a man you love is an experience of equal abjection to repeated physical and psychological violation by a stranger? Really?

Another source of dismay: when a bit of contractual muddiness surrounding the original battlefield marriage gives Lily her opportunity to seize control of her life, this seizure emerges as ... a makeover narrative. Sprightly, unusual, battle-formed Lily learns about fashion, music, manners. She takes dancing lessons. Crucially, she learns to read. But the vast majority of what she learns is fairly cosmetic, and I can't help but feel (with Kilbourne) that it blunts every unusual and lovable aspect of her. What we end up with is a heroine who was once unpredictable and interesting and is now merely immature and "fresh."

Much more interesting is the secondary romance involving an older gentleman who shows a pointed interest in Lily and a widely beloved spinster who takes our heroine under her wing. This was a relationship that I wanted to explored over the course of a whole book: they are both independent agents, self-sufficient and self-respecting, reluctant to give up their freedom for marriage. Their friendship is so constant, longstanding, and close that everyone has left off speculating about their romantic potential. These two were so much more interesting (and adult) than the primary couple, but their developing relationship is mostly an afterthought in the novel. At a certain point I found myself reading on solely for the rare tidbit I would get about the two of them.

Kudos to Balogh for acknowledging that Lily's wartime violation had lasting effects on her response to sexual intimacy, and that her reintegration into marriage, family, and society must of necessity be painful and halting because of the abandonment and violence she has encountered. Although Kilbourne couldn't have known what she was going through, there's an inevitable sense of betrayal that Lily experiences that felt both realistic and emotionally complex to me:

All the time she had been with Manuel and the partisans, clinging to the hope of one day returning to the man who had married her, he had been courting another woman, perhaps falling in love with her. All the time she had been making her difficult journey, with only the thought of reaching him sustaining her, he had been planning a marriage with someone else. (96-7)There's a price to a life of insulating privilege, pleasure, and affection (like the one I have to admit I lead), and it's the betrayal of those who are suffering just out of sight. The betrayal of forgetting, of overlooking, of never speaking. There's a price to doing merely what is expected of you, and Kilbourne pays it in spades. His struggles (since he is an essentially ethical man) over this crime of omission are the best part of the novel.

But there's also something very uncomfortable about the treatment of rape here, albeit something that might have a great deal of historical and psychological truth to it: Lily is convinced, like many victims of sexual assault, that she bears a measure of responsibility for what happened to her, for not fighting hard enough, for not resisting to the end. In fact, she is convinced that she is an adulteress (a conviction that complicates her sense of betrayal that Kilbourne has been courting another woman while she was in Manuel's power). Even relatively late in the novel, there is a scene in which our hero "forgives" her for what happened in Spain, despite the fact (he insists) that she has done nothing that requires forgiveness. Eurgh. I found myself wishing for just one more layer of ethical context - perhaps a little more psychological depth and complexity from Lily - in scenes like this, to keep my skin from crawling with alarm. The fault is so unbalanced between the hero and heroine, so unquestionably NOT on her side, that it rankled to see her assume blame in even a qualified way for what happened.

What say you? Is there a Balogh I should read that both begins and ends well? That sustains its initial levels of urgency and complexity throughout its several hundred pages?

|

| Moon over Farfara |

Scribbled in the back of my copy of The Name of the Wind by someone who hadn't slept in 36 hours, from a plane over Maritime Canada:

8.26.11

The last sunset I saw was two days ago, my feet in the sand of Waikiki beach. This one's above the clouds over Nova Scotia. The Hawaiian sunset's five minutes of silvered waters and blushing skies; the Haligonian's a half hour of blunt volcanic intensity, slowly swallowed by soot.

Maybe it's homesickness, but I can't say which I prefer, which I more admire.

|

| Sooty skies (A shorter exposure of the same shot.) |

I've got a bit of a blog backlog building up. The reason? I'm back in Farfara and the term's about to begin. Turns out that it's the perfect formula for overwhelming chore-doing.

But I may have a bit of a triage problem. There are syllabi that need to be finalized but instead I find myself doing VITALLY IMPORTANT things like this:

|

| Putting up the hammock. Now we just need to get a chainsaw so that we can clear up that view of the ocean. |

|

| I am a stenciling queen! La Divine Sarah is unimpressed. |

Which means, [cough], that I need to get back to working on my syllabi now.

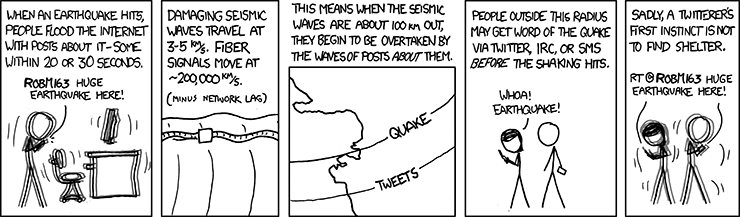

When I woke up this morning, I learned about my hometown's earthquake via Twitter as it happened. (In Honolulu it's, well, exactly like every other day of the year in Oahu. Balmy and peaceful.) I called my mother in Washington to see whether she felt it. "YES!" she said, "I rushed in to protect the Italian plates, which were rattling on the shelves. Then I thought, 'wait - this isn't a good idea,' and ran out the door."

|

| More than just playwrights are buried here. |

My friend W sent me this tale of barebreasted nineteenth-century female duelists, wondering why it is that every time he comes across a story about sexualized eccentricity, he thinks of me.

|

| These ladies really know how to accessorize a topless duel. And, of course, you can't go to a duel without samba pants. What was the lady in blue thinking? |

I really couldn't say, W, but I like to think that wherever in the world people come across dashing displays of Amazonian honour, they think of Sycorax Pine.

[cue swelling theme music here.]

My grandparents celebrated their 68th wedding anniversary this week. Sixty-eight years, people. When I exclaimed over this to their best friend of many years, she made a shrugging gesture that was somehow audible over the phone: "You know, the first sixty-eight years are the hardest."

My grandmother's reflected, indirectly, on the secrets (challenges?) of a long marriage when I called her on the day itself: "I'm trying to be less sarcastic, which is hard, because it's been my characteristic form of humor all these years." She adopts an ironic tone: "Or what I thought of as humor. It remains to be seen whether it was or not."

You may remember that I spent some time with my grandparents a few weeks ago in Washington. While there, I spent some time updating my grandmother on my friends' lives. Many of them are pregnant, and my grandmother began to tell me what childbirth was like in 1946.

"I gave birth in a municipal hospital in Oklahoma run by nuns, if you can imagine such a thing. Every element of it is improbable on its own," [Why? I don't know.] "but put them all together.... Of the dozen wives in our little group, only one wasn't pregnant."

Me: "Yeah, it was the baby boom."

My grandmother: "No, it was Oklahoma, and there was nothing else to do."

I might have done a double-take, except that this isn't an unusual sort of witticism from my grandmother.

Me: "Er, I would have thought it was more about the return of the absent male population. The baby boom, right?"

My grandmother: "Yes, I suppose it couldn't have been as boring as Oklahoma everywhere, all at once." [Wry smile.] "Yes, the war ended and we all jumped into bed."

Sycorax Pine: Oh my god, D. I want these SO MUCH.

D: What are they?

Sycorax Pine: False eyelashes. They're cut according to traditional Chinese motifs. See, these are peonies. And these are tiny horse heads!

D: Honey... [He leans in close, and whispers tenderly in my ear.] They're abominations.

|

| On what occasion would I wear these, you might ask? The eyelash makes its own occasion, I'd reply, with a repressive glare and a flirtatious bat. |

Everything on my stunning friend shannonpareil's tumblr (Holy Crap, A Talking Biscuit) has been graceful and longing-inducing lately. When we were teenagers, we used to write verse (sonnets, free verse, sestinas) while bored in class, trade them in the hallways between periods, and each complete the other's poem in the next class. She's that kind of friend.

I give you two reflections on love, courtesy of her. This:

things i pretend

- you are on a trip.

- you are on a trip to the amazon in search of el dorado.

- you are on a trip to the moon.

- you are on a trip anywhere that is beyond the range of modern communication.

- you are a character in a book i fell in love with, but now the book has ended, and you only live in the pages.

- you’re just in the other room while i stand in the kitchen cooking dinner.

- i haven’t met you yet.

I'm not sure how to feel about Farfara's new lawn. (Mère Sycorax, looking at pictures of my new garden: "Would you really call that a lawn?" SP: "Yes." Mère Sycorax: "Really?") It's scraggly, starved, and unkempt. Except where it covers our vast septic field; there it's lush, verdant, and self-satisfied.

When D and I bought the house, we were somehow convinced that it was a small lawn. But we weren't taking into account the scale of greater Farfara's twelve acres. In fact, the grassy section is considerably larger than any lawn we would have gotten with a city lot.

D: "You know what show's supposed to be good? My Little Pony. Seriously: google it."

He gradually becomes aware of a creeping silence.

D: "What? WHAT?"

I'm not kidding; he's making me watch it online. I'm going to see whether I can't tempt him back to sanity with this box set of Homicide.

Sycorax Pine: "Why are you so uncaring?"

D: "I'm totally caring. It's just that your problem's not that big of a deal."

Ladies and gentlemen: my relationship.

Just to be clear, my problem was a total lack of chocolate in the house. I put it to you: what kind of a mind doesn't think that's a big deal?

Oh, how I covet this.

|

| Chia ring! |

Why? Why do I want it? It promises to be nothing but heartbreak, given my Darwinian attitude to both plants and jewelry. But something about it just cries out boho-Galadriel charm to me.

Even if I would have to spend the whole day obsessively extending my hand (see picture) while fending off potential ring-harmers with vicious stares. (Not Galadrielesque, you say? Did you see her thinking about taking the ring of power?)

If only I didn't have a mortgage, this is exactly the sort of investment I would make. So it's lucky that I've sunk my worldly wealth into property, because I'm not sure a portfolio of living jewelry's going to support my retirement plans.

While we were in London, D found something like this Bookcase wallpaper the glorious Dorky Medievalist sent me. (I covet it. Perhaps for the guest bathroom?) When D discovered it, it was like a whole new realm of strategy opened up in his war on my library. He became very excited: "How 'bout we just get rid of all the books and replace them with wallpaper that LOOKS like books?"

There followed an acid pause.

Then I said, "I've consulted with the books, and they think I should buy D wallpaper for every room and get rid of YOU."

Pop quiz. Which of the following things did Sycorax Pine see or step over on her walk home from the library yesterday?

- A mongoose

- A gecko

- a desiccated gecko skeleton

- a full 180 degrees of rainbow

- a toilet in the middle of the sidewalk

Mongoose: 'Let's go to the library.'

Gecko: 'No, look! There's a rainbow to follow.'

I'm in Hawai'i again (without having caught up on my London blogging - curse it!), where, as I may have mentioned, my partner D works. He has long days of filming, I have somewhat shorter days at the University of Hawaii library doing course prep and research.

I'm fairly sure that my mental processes are exactly reversed in Oahu,"transformed and inverted," as King Shudraka says in the Sanskrit drama I spent the afternoon reading, "even as an image reflected in a mirror is reversed so that the right becomes sinister."

Twice this week I've embarked on the fifty minute walk home from the UH library just as it started to rain at some length. Both times I thought, "Oh good, this will make the walk pleasanter, and my hair will look better when I get home." Both times this mental statement was untouched by even the slightest trace of sarcasm.

|

| The effects of the rain |

Who is this curly-hair optimist living in my brain???

“‘Look at you,’ he murmured almost to himself. ‘You’re a baby, nothing but a moment, a heartbeat.’

She took a quivering breath. ‘I’m more than that.’” (67)

The dragon, Cuelebre (his friends call him Dragos), is one of the oldest and most powerful creatures in this world or any Other one, and he’s, to use the mildest possible term, a collector. He likes his things, and he knows them well. When he finds that someone has, for the first time in the eons he’s been hoarding, penetrated his defenses, he’s filled with rage. When he finds what’s been taken - a single penny - he’s puzzled. When he reads the note Pia left (Apologies! I left a replacement penny, so no hard feelings!), he’s bemused despite himself.

The dragon, Cuelebre (his friends call him Dragos), is one of the oldest and most powerful creatures in this world or any Other one, and he’s, to use the mildest possible term, a collector. He likes his things, and he knows them well. When he finds that someone has, for the first time in the eons he’s been hoarding, penetrated his defenses, he’s filled with rage. When he finds what’s been taken - a single penny - he’s puzzled. When he reads the note Pia left (Apologies! I left a replacement penny, so no hard feelings!), he’s bemused despite himself. “His head jerked up. He had one of the most startling and unwelcome thoughts of the last century.

Am I a boyfriend?” (203)

“‘If someone swears and oath of his own free will, the binding falls into the realm of contractual obligation and justice. I can do that. And have as a matter of fact,’ the other woman said. She moved toward the back of her shop. ‘Follow me.’

Pia’s abused conscience twitched. Unlike the polarized white and black magics, gray magic was supposed to be neutral, but the witch’s kind of ethical parsing never did sit well with her. Like the relaxation spell in the shop, it felt manipulative, devoid of any real moral substance. A great deal of harm could be done under the guise of neutrality.” (15)